Why Are There So Many Naked People in Art

Why the nude still shocks

(Image credit:

Tate/Art Gallery of New Southward Wales

)

A new exhibition explores art's long fascination with the naked form. Why practice representations of the human body continue to cause controversy? Sam Rigby finds out.

T

The nude has fascinated artists and viewers alike for centuries – even today it continues to be a discipline that triggers debate and controversy. The unclothed homo body is one of fine art'southward greatest subjects. It has appeared in almost every major art movement from Cubism to Abstract Expressionism to the political art of more recent times. Why does the nude continue to fascinate u.s.a.? That'south the question posed past a new exhibition, Nude, at the Art Gallery of New S Wales in Sydney, which opened before this month. Information technology brings together 100 portrayals of the nude from the Tate's drove, including paintings, sculptures, photographs and prints from the tardily 1700s through to the nowadays 24-hour interval.

William Strang, The Temptation (1899)

(Credit: Tate/Fine art Gallery of New S Wales)

"The nude fascinates us for a very simple and quite profound reason and that is that information technology'south fine art about us. We all have a body; we're all fascinated bodies and bodies in the unclothed state," curator Justin Paton tells BBC Culture. "The exhibition is a journeying through the many different human being feelings and emotional states, and that for me is what is most compelling well-nigh the nude as a subject field."

William Strang'southward late-19th Century work The Temptation takes us back to one of the primal stories about nakedness in Western culture – the story from the Volume of Genesis in which Adam and Eve became aware of their unclothed bodies. "Out of that comes the mod nude and our anxieties and our excitement about what lies nether clothes, which are the two fundamental impulses that has driven the nude throughout its history," explains Paton.

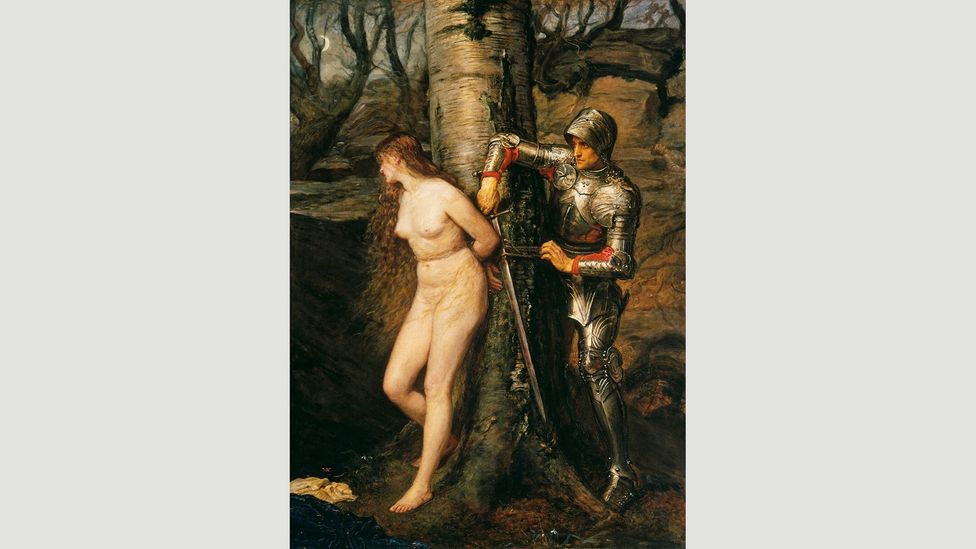

Sir John Everett Millais, The Knight Errant (1870)

(Credit: Tate/Fine art Gallery of New South Wales)

When nosotros think of the nude, many of u.s. may carry in our minds a classical image of the heroic, sculpted bodies that dominated 19th-Century art, just equally Paton points out, "the nude is actually an ever-changing and endlessly contested form". In many ways, gimmicky portrayals of the naked body differ vastly from Victorian works, simply there are likewise strong similarities.

"The debates about honesty and idealisation from the Victorian period reflect correct through to our own time, which I recall resembles the Victorian period in quite striking ways, specially when yous look at the fashion nudity and body issues are discussed in the culture at large," he says. "Even today there is this amazing mix of prudity and permissiveness. We're then used to seeing millions of images of the naked human course, yet at the aforementioned time a unmarried nude artwork in a gallery tin can still testify extraordinarily controversial at times." Only recently in Australia, an art magazine was compelled past its publisher to conceal the nipples on a female nude painting it had chosen for its cover.

The Knight errant is an example of what scholars refer to as the 'English nude', which caused controversy in the late 19th Century because the subjects of these works were deemed too lifelike. "It betrayed its origins, where a painter had obviously stood in front of a existent, live female torso, and was non concealing that fact sufficiently."

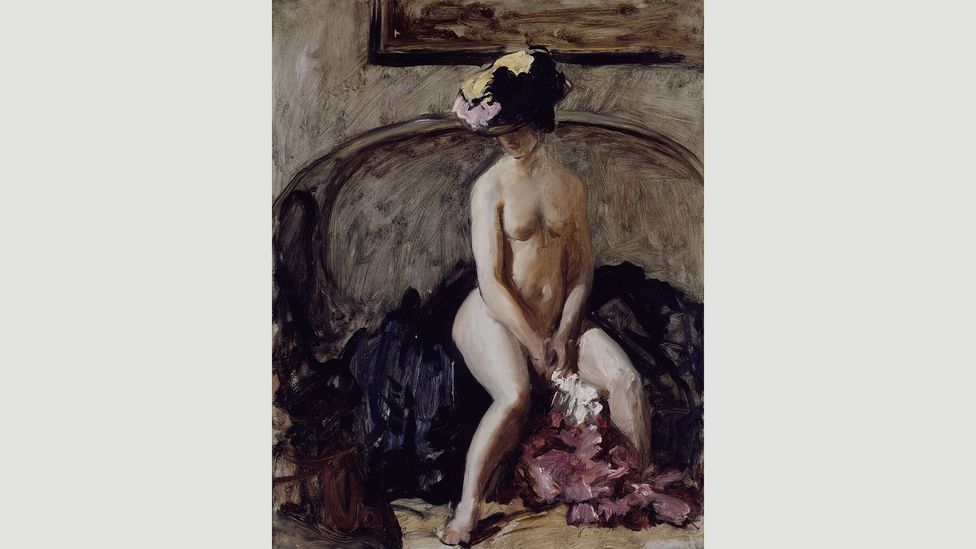

Philip Wilson Steer, Seated Nude: The Black Lid (c1900)

(Credit: Tate/Art Gallery of New Due south Wales)

Can a nude actually be besides lifelike? Nudes of classical figures like Psyche and Venus tin be appreciated purely as art, without having to consider the living, breathing human that sat earlier the artist. This discomfort with recognisable, everyday people as the subject of nude portraits was but accentuated in the 20th Century as the nude entered the domestic space, with paintings of bodies actualization in bedrooms or studio interiors. Philip Wilson Steer's portrait from the plough of the century is a perfect example of how one pocket-size detail tin can make a piece of work controversial. When John Rothenstein, visited Steer in 1941 and chose the painting for Tate's collection, Steer informed him that he had chosen not to showroom the painting during his lifetime, as his friends had felt information technology to be indecent. "The reason they felt this style was non considering the adult female was nude, but because she was nude and wearing a hat," Paton says. "This was seen every bit somehow accentuating the nudity in a fashion that was not completely seemly." A unproblematic hat, seen on many women of the fourth dimension, was enough to push the painting out of the world of the platonic and into the realm of the erotic.

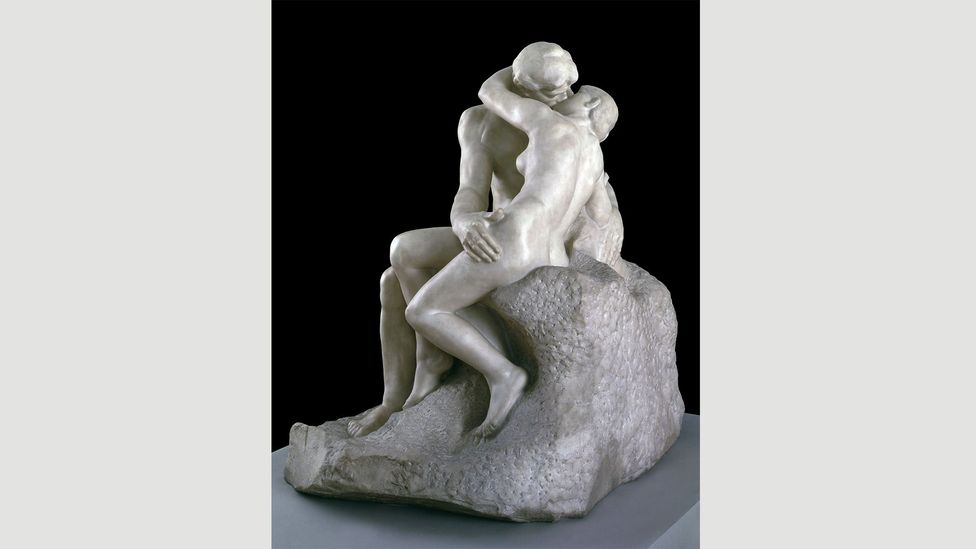

Auguste Rodin, The Osculation (1901-04)

(Credit: Tate/Art Gallery of New Due south Wales)

It'south one of the well-nigh famous images of romantic love, and it'due south the star attraction of the exhibition in Sydney – having travelled beyond Europe for the very showtime time. "A kiss is a very private and intimate moment between two people, and what is genius about Rodin's work is how often the buss is actually hidden from us by the limbs or torsos of these figures," Paton says. Rodin demonstrates the intense concrete and emotional connection between these two naked lovers in a number of means: the rippling muscles of their backs, the fashion their legs ride upwardly over each other, and their easily. It's the couple'due south hands that Paton believes most worthy of attending. "Their hands feel large relative to the calibration of their bodies. When we are in love and when nosotros embrace that person, our sense of bear on is heightened," he explains. "Rodin is telescoping those sensations past drawing our attention to the hands of these figures."

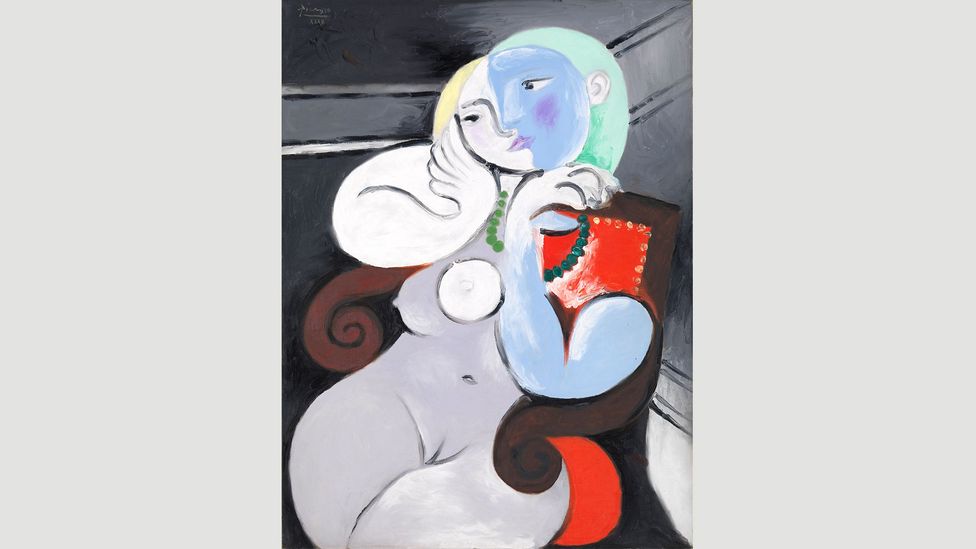

Pablo Picasso, Nude Woman in a Scarlet Armchair (1932)

(Credit: Succession Picasso/Tate/Fine art Gallery of New S Wales)

The power of an embrace between two lovers is likewise the focus of Picasso's Nude Woman in a Carmine Armchair (Femme nue dans un fauteuil rouge) from 1932 – although it might non be immediately credible to the untrained centre. While the painting initially appears to be of a lone woman, Marie-Thérèse Walter, one of the creative person's many muses, a closer look makes you lot realise that two people inhabit this piece of work. "Within her face is the shadow of a male confront, which seems to press in for a kiss from the right," Paton argues. "The arm on the right hand side of the figure strangely seems to disassemble from the trunk of the woman and joins the dorsum of the chair, which starts to read equally the torso of a male figure who is embracing her." He sees information technology every bit an illustration of how it feels to be completely consumed by someone, to the indicate that it becomes incommunicable to distinguish where ane person begins and the other ends. "It's an amazing expression of how it feels to be deeply in love, to the extent that you are fused in the moment of embrace."

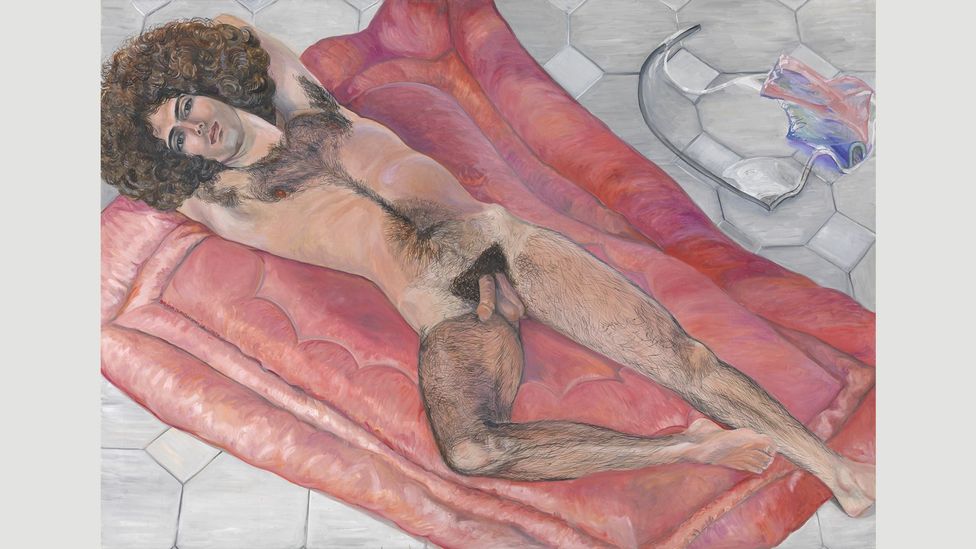

Sylvia Sleigh, Paul Rosano Reclining (1974)

(Credit: Tate/Fine art Gallery of New South Wales)

With the advent of feminism, female artists turned the tables on tradition in the later on decades of the 20th Century, painting male subjects equally the subject of the female gaze. This painting came in the same twelvemonth that the Australian magazine Cleo included its showtime ever male person centrefold, and it is representative of a bigger shift in the nude more than mostly. "Sylvia Sleigh was forthright in saying she wanted to paint sexy men for women to expect at, but the painting isn't leering," Panton says. "It's tender and warm, and reflects the fact Sylvia knew this homo": the musician Paul Rosano, who posed for Sleigh on more than one occasion. "Her affection for him and her enjoyment of how he looks is apparent particularly in the body hair, which she renders stroke by stroke," he adds.

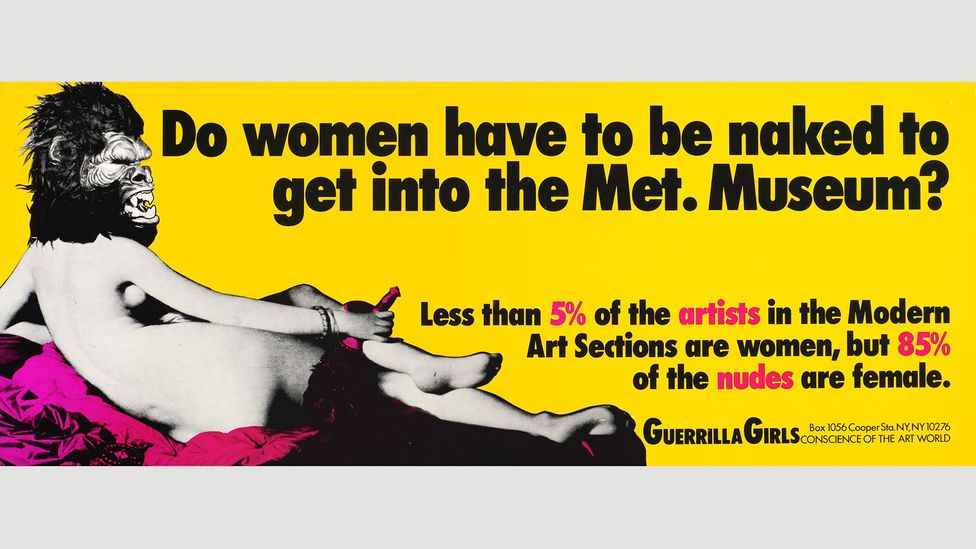

Guerrilla Girls, Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get into the Met Museum? (1989)

(Credit: Guerrilla Girls/Fine art Gallery of New South Wales)

The arrival of the women's art movement too brought with it the protest nude. These new artists looked at the nude through new eyes, and questioned everything that had come up before. This protestation piece from the Guerrilla Girls – which takes one of the well-nigh famous nudes in art history and turns her into a feminist masked avenger – comes from a pivotal moment in the history of the nude, calling out the lack of female artists in New York City'southward Metropolitan Museum of Art in comparison to the wealth of female nudity on display. It'southward an paradigm that has enjoyed many lives since information technology first appeared on the side of a city bus – where it unsurprisingly made waves. "The image was soon removed from the bus and the lease the Guerrilla Girls had taken out on it was terminated every bit information technology was deemed likewise provocative," says Paton.

It was a ruling that was at once both infuriating and satisfying. The majority of complaints focused not on the unclothed female body, but on the pink fan held by the figure, which the Guerrilla Girls had modified so that information technology became unmistakably phallic. It proved a point the group had set out to make: the public is comfortable exposing female bodies, only the same doesn't use to the male course. "Information technology is arguably the almost influential nude created in recent decades," says Paton.

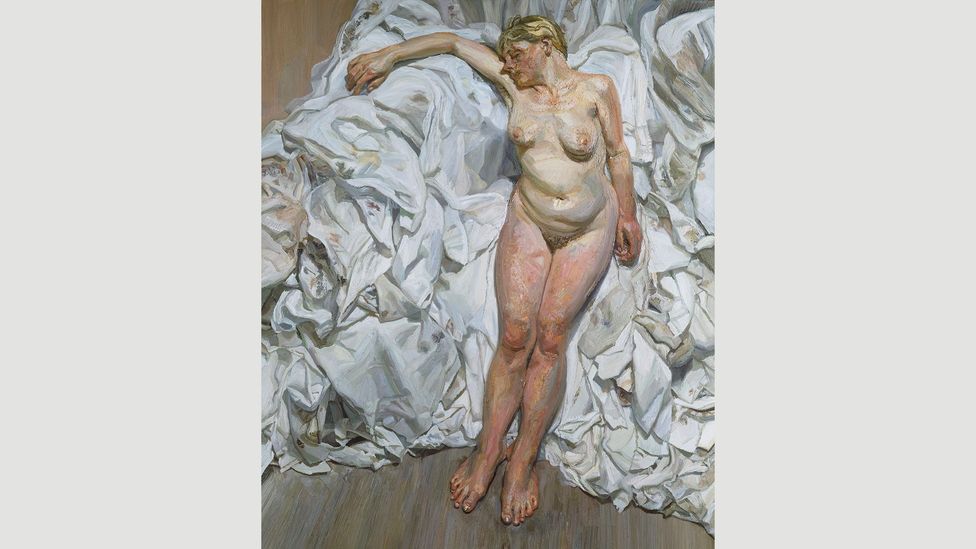

Lucian Freud, Standing by the Rags (1988-89)

(Credit: Estate of Lucian Freud/Tate/Fine art Gallery of New South Wales)

"Freud is one of the greatest painters of the nude in contempo years, and I recollect chiefly, he's also one of the best painters of the naked," Paton says. Is there really a departure betwixt the naked and the nude? According to art historian, Kenneth Clarke, there is. He said that while the nude is an idealised body that appears to exist comfortable appearing unclothed, the naked is a body that has been exposed and deprived of clothing. The exhibition features examples of both, but Paton believes Freud's piece of work lies firmly in the naked camp. "He chosen many of his paintings naked portraits, and there's a sense that he's letting us know that the painting is telling a raw truth about what it is to exist human and have a torso," he says.

Freud always insisted on having a live model in front end of him, and the experience of sitting for him is conspicuously shown in Continuing by the Rags, a terrific example of his late style. "You tin get an extraordinary sense of the challenges of existence one of Freud's subject, because the model is posed in a way that suggests both a land of sleep and abandonment, just also astute physical force per unit area," he explains. This is particularly evident in the oversizing of her feet and lower legs, which appear to be supporting her weight. While this piece of work is certainly an example of the naked, it as well evokes the nudes of the past. "The manner her arm is out flung reminds me of some of the quite elaborate poses that nudes would occupy in the 19th Century, where they might be cast in the role of a famous hero," says Paton. "Freud's hero is very much of our earth, only she still has echoes of these older artists."

Louise Conservative, Couple (2009)

(Credit: the Easton Foundation/Tate/Fine art Gallery of New South Wales)

Critic Lucy Lippard in one case wrote that Louise Bourgeois portrays bodies from within. "No matter what material she uses, her work e'er delivers an under-the-peel sensation," Paton adds. "Information technology brings dwelling house what vulnerable and fragile beings we are, while too conveying the amazing vitality and bulldoze of the human being brute." This work in gouache and pencil on paper reduces the homo body to its simplest form, with flashes of bluish placing on accent on the reproductive organs. According to Paton, the thin, watered downwardly advent of the pink pigment is besides evocative of "the volatile fluids of life… It's suggestive of life blood, a mother'due south milk and even amniotic fluid," he says. In Couple, it'due south as if we're looking right through the peel to the inside story virtually what makes the trunk thrive and survive – you lot don't become much more nude than that.

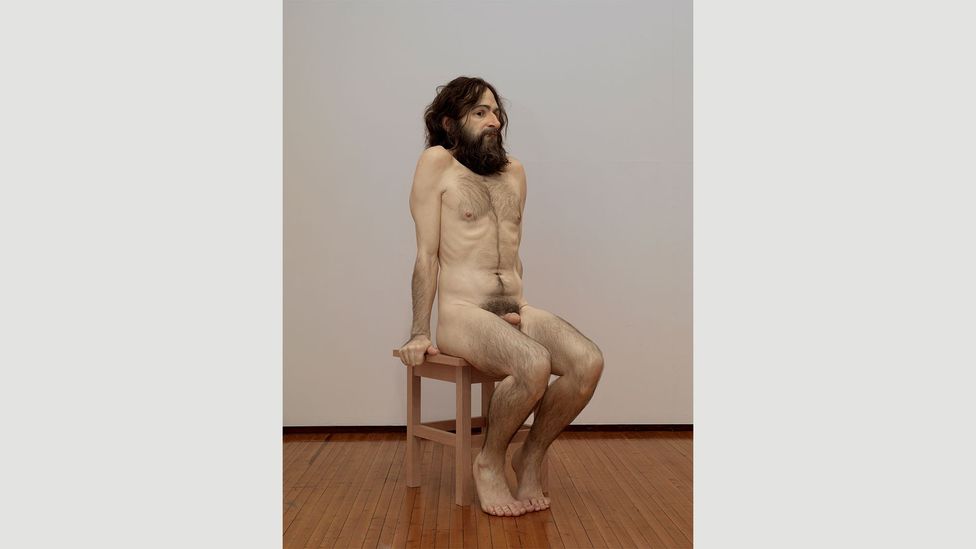

Ron Mueck, Wild Man (2005)

(Credit: Tate/NPG Scotalnd/Marcus Leith/Art Gallery of New South Wales)

The more than lifelike a nude is, the more controversial it seems to be. Ron Mueck'southward recent works are eerily realistic, and often get out the observer feeling uncomfortable without being able to articulate why. "One result of the sculpture being and so lifelike is that people audibly yelp when they first see information technology," Paton says. "He is not a god or warrior – he has no literary alibi to hide backside. He is just a man in a state of complete exposure." Wild Man but serves to demonstrate how ill at ease nosotros still are with the naked form, particularly when we tin can't separate ourselves from the field of study on show. "In the finish this is a sculpture about how it feels to be looked at," the curator suggests.

Artists working with the nude today are eager to remind u.s.a. that looking at bodies is ever a charged and very personal act. In many means, our guild is desensitised to naked bodies. We meet them everywhere, only they are often hiding behind something – a character they are playing, a perfume they are selling, or a cause they champion by exposing themselves. But in a work like Mueck's, at that place is zero to hide behind. Information technology's the human being in its barest form, and that it is something we may never become used to seeing. Equally Paton rightly points out: "The nude is no i affair – information technology's a question rather than an reply, and that question reverberates in our fourth dimension."

If you lot would like to comment on this story or annihilation else y'all have seen on BBC Culture, caput over to our Facebook page or bulletin us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "If Yous Only Read half-dozen Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Civilisation, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Fri.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20161129-why-the-nude-still-shocks

0 Response to "Why Are There So Many Naked People in Art"

Post a Comment